This post is an experiment with publishing a paper in reduced HTML form – I’m curious to see if it more people find it this way.

To cite this article:

Kelly N., Clara M. and Kickbusch S. (2015) How to develop an online community for pre-service and early career teachers, ASCILITE 2015, Perth

Why an online community for teachers?

There are many challenges to beginning a career as a teacher (Veenman, 1984). Support during this period of transition into service is critical and is particularly useful in the form of mentoring and induction programs (DeAngelis, Wall, & Che, 2013; Ingersoll & Strong, 2011). Online communities are a form of support that have the potential to stimulate collegiality between pre-service and early career teachers (PS&ECTs) (Herrington, Herrington, Kervin, & Ferry, 2006; Kelly, 2013). This paper aims to present design principles from ongoing[1] design-based research aimed at creating an online community of PS&ECTs across multiple institutions in the state of Queensland (Kelly, Reushle, Chakrabarty, & Kinnane, 2014). It is structured by presenting theoretical background and the argument for why there is a need to design and develop a new type of community for PS&ECTs; and then articulating strategies for how to develop such a community.

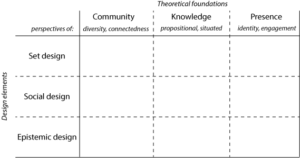

There have been a number of recent attempts to augment the support for pre-service and early career teacher with the formation of online communities (e.g. Herrington et al., 2006; Lee & Brett, 2013; Lin, Lin, & Huang, 2008; Maher, Sanber, Cameron, Keys, & Vallance, 2013). Such attempts typically adopt one of three complementary paradigms, each of which make a commitment to valuing the connectedness between learners: (online) communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, White, & Smith, 2009), connected learning (Ito et al., 2013) and networked learning (Goodyear, Banks, Hodgson, & McConnell, 2004). In this work we will refer to online communities with an understanding that they can be viewed through any or all of these lenses which place the emphasis respectively (and arguably, given the diversity of views that each term has come to represent) upon:

- (communities of practice) The cultural norms and collaborative relationships that emerge within a group of practitioners with common purpose, where “communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (Wenger, 2011).

- (connected learning) The open nature of learning in a connected world allows for learning to be authentic and linked with society beyond classroom walls to promote interest and hence learning, where connected learning is “embedded within meaningful practices and supportive relationships” and is committed to recognising “diverse pathways and forms of knowledge and expertise” (Ito et al., 2013)

- (networked learning) Learning is understood to take place through connections of learner-learner and learner-resource and this connectedness can be greatly enhanced through technology, where networked learning is “learning in which ICT is used to promote connections between one learner and other learners; between learners and tutors; between a learning community and its learning resources” (Goodyear et al., 2004)

In short, research in these paradigms has shown that online communities of members with a shared practice can be extremely useful. They bring together in one place the people that a practitioner is likely to draw upon for questions about practice. They support the creation of such connections. Through interaction, they facilitate the development of rich stores of (third person, represented) knowledge that is accessible to all members. Whilst online communities can be a part of formal education or professional development, they are often informal.

Globally, there has been a trend towards the adoption of online communities in which the term social network has become the successor to ‘Web 2.0’ (boyd & Ellison, 2007). Many professions and groups of practitioners now have online communities associated with them; and some have even transformed the nature of the practice associated with them (e.g. Mamykina, Manoim, Mittal, Hripcsak, & Hartmann, 2011). Large scale communities (with hundreds, thousands or even millions of members) offer the potential for facilitating valuable connections within the profession. This may be between members (e.g. a beginning teacher in a remote school might be connected with another beginning teacher in a similar situation) or between members and resources – the larger the network, the more likely that the individuals or resources needed can be found. There is, however, a trade-off with social presence and engagement being challenging to achieve in larger communities (Clará, Kelly, Mauri, & Danaher, In press).

In this context, our argument is that large scale online communities have much potential to support PS&ECTs that is yet to be fulfilled. Firstly, what are the needs that PS&ECTs have from an online community? Six categories for the ways in which teachers can support one another online can be drawn following the work of Clarke, Triggs, and Nielsen (2014): (i) supporting reflection; (ii) modeling practice; (iii) convening relationships; (iv) advocating practical solutions; (v) promoting socialisation within the profession; and (vi) giving feedback. Many existing platforms that are used by PS&ECTs successfully enable teachers to convene relations, promote socialisation and advocate the practical. However, there is a dearth of large scale sites (i.e. more than 200 users) that promote reflection, feedback and modelling of practice. This is perhaps due to teachers feeling a need for privacy (a closed online space), trust (in other members of the community) and some kind of stability (in membership of that community) that is not met by the current generation of large scale online communities of PS&ECTs (Clará et al., In press). Early results from current work by the authors analysing the interactions of teachers in Facebook supports this hypothesis.

There are many existing large scale online communities for teachers within Australia, however none fills all of these needs of PS&ECTs. Whilst an empirical survey of these communities is required to fully substantiate this claim, some types of online community available in Australia can be identified, Table 1, and limitations based upon anecdotal evidence described. “Scootle Community” is a national, government funded site that appears to have low levels of engagement and social presence amongst users, with low level activity on the site given the pool of potential users, possibly due to a lack of stability (constantly changing users), privacy (all data is owned by the government and is visible to all members) and, hence, trust. The Queensland state government supported site “The Learning Place” comes closest of the examples given to fulfilling the potential of online communities to meet PS&ECT needs. It has high levels of activity, with many widely-used resources that are the focus of discussion and for facilitating connections between users. However, the state government (who also employ many of the teachers using the site) owns the data and is heavily visible through logos and announcements on the site. This, along with broad visibility in most sections of the site, might be limiting trust for users of the site to share details of practice. There is little evidence of teachers developing the close connections needed for reflecting on practice, providing feedback or modelling practice (however, this may be occurring in private channels of communication). Many groups of PS&ECTs have arisen on the commercial platform “Facebook” (and similarly on “EdModo”). Some groups are visible and massive, whilst many are small and private. There is much variation between groups, however they have in common that: (i) the knowledge developed by the community is not searchable or reusable and, hence, is lost; and (ii) each new group springing up begins anew, losing the benefits of having a large established community. Many teacher education institutions also have their own intra-institutional online communities that can often support highly engaged, collegial support – however they are limited in size, cannot facilitate cross-institutional networks and are susceptible to fluctuating support from their host institutions (e.g. funding changes or key staff leaving).

Table 1: Types of online communities used by PS&ECTs in Australia with examples

| Type of community |

Example of community |

Description of example |

| Nationwide, government funded |

Scootle Community

http://community.scootle.edu.au

|

Federal Government supported site (run by Education Services Australia) to facilitate a social network (Facebook style) around Scootle resources in particular and the teaching profession in general. Available to most educators in the country. |

| Statewide, government funded |

The Learning Place

http://education.qld.gov.au/

learningplace/ |

State Government supported site (run by Education Queensland) with a large and widely used collection of resources for classrooms and professional development, with social network support (chat, blogs, learning pathways) |

| Commercial |

Facebook groups

https://facebook.com |

Widely-used commercial site that supports many diverse groups of teachers. Some are openly available and some are private; ranging from the very small to the very large. |

| Institutional |

Education Commons (USQ)

https://open.usq.edu.au/course/

info.php?id=62 |

A Moodle community of PS&ECTs supported by motivated faculty members who provide a library of articles, videos and mentoring through the site (Henderson, Noble, & Cross, 2013). |

Design principles for “TeachConnect”

With this understanding of the gap that remains, a group of academics from universities and teacher education providers across Queensland are working together to develop a community, TeachConnect, which will be launched in September 2015 and supported by the Queensland College of Teachers and an Office of Learning and Teaching grant. TeachConnect aims to augment current support for PS&ECTs by filling in the gaps identified above. A number of design principles for developing the site can be listed as:

- It is independent and data (e.g. conversations) are private, owned by the members of the community – this is reflected in the lack of institutional presence (e.g. logos) on the site and the focus upon the profession (e.g. inspiring quotes about education).

- It is single purpose (i.e. doesn’t have to meet government or institutional priorities) and its appearance and design make it clear that its goal is to facilitate PS&ECTs supporting one another.

- It is free and universal in that all teachers have access to the site, regardless of school system or status of employment.

- It is also restricted to individuals who have at some point been a pre-service teacher, to maintain the focus upon developing professional practice.

- Knowledge that can be separated from its context and proponent is co-created and re-usable (e.g. where to find resources, how to get accredited, how to navigate schools) and develops over time.

- There is a two-layer design that has clearly defined separation between what is publicly visible and a trusted, private space which is the focus of the site, where close relationships can develop, allowing for reflection upon practice between peers and facilitated by experienced teachers (a type of mentorship).

- It is designed to be simple, quick and easy to use so that there is a minimal threshold to overcome to commence using the site (one-step sign on facilitated by close co-ordination with universities).

- It is possible because it is widely supported by many universities within Queensland. It relies upon the shared purpose that all schools of education have in wanting the best possible outcomes for PS&ECTs, is inclusive in design and is freely accessible by all teacher education institutions.

The process of developing TeachConnect: Lessons learned

The process of developing TeachConnect has followed the principles of design-based research through multiple iterations of design involving the input of participants (Barab & Squire, 2004; Collins, Joseph, & Bielaczyc, 2004). The design-based paradigm is a good fit for this work, as educational research is heavily context dependent, and at the same time the literature on developing online communities suggests that the exercise is far from being an exact science. Some heuristics for developing any kind of online community were distilled by Shirky (2010) as: (i) start small with a core community, as if you rely on being big it will probably never happen; (ii) understand and provide for what motivates your members (both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation); (iii) use the default options in the platform wisely to promote social connectivity; (iv) cater for all types of engagement (e.g. lurkers as well as active participants); (v) have as low a threshold as possible to get started on the site; (vi) tweak as you grow and be responsive to what the community is asking for.

The vision for TeachConnect was informed in part by the literature, but also through focus groups (with PS&ECTs, teacher educators, experienced teachers and stakeholder organisations), a survey (Kelly et al., 2014; N=183) and a pilot study. Whilst details of this pilot and the development of TeachConnect are forthcoming, the essence of the lessons learnt can be distilled here. A pilot of a platform for PS&ECTs was conducted in 2014 (www.TeachQA.com) and involved over 200 pre-service teachers across two universities, and over 20 experienced teachers to develop a community. An evaluation of the problems experienced in this site revealed that it was: (i) Too difficult to sign up to; (ii) too restrictive in interactions (with not enough opportunity for dialogue; (iii) too public and did not allow for trust to develop (no private spaces for interaction); and (iv) not enough community engagement to remind PSTs that the site existed.

In response, the TeachConnect platform is being integrated with a schedule of community engagement. Researchers will travel and talk to the lecturers, pre-service teachers and teachers who will be using the platform to build the community. The platform will be strongly customised to be specific to teachers’ needs, rather than using something “off-the-shelf”. We plan to work with an initial group of dedicated users to build a group culture, and help them as they do this. Ultimately, the use of the platform will only spread if it is fundamentally useful – there are no short cuts for building an online community.

References

Barab, S., & Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 1-14.

boyd, d. m., & Ellison, N. B. (2007). Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. Journal of Computer‐Mediated Communication, 13(1), 210-230.

Clará, M., Kelly, N., Mauri, T., & Danaher, P. (In press). Challenges of teachers’ practice-oriented virtual communities for enabling reflection. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education.

Clarke, A., Triggs, V., & Nielsen, W. (2014). Cooperating Teacher Participation in Teacher Education A Review of the Literature. Review of Educational Research, 84(2), 163-202.

Collins, A., Joseph, D., & Bielaczyc, K. (2004). Design research: Theoretical and methodological issues. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13(1), 15-42.

DeAngelis, K. J., Wall, A. F., & Che, J. (2013). The Impact of Preservice Preparation and Early Career Support on Novice Teachers’ Career Intentions and Decisions. Journal of Teacher Education.

Goodyear, P., Banks, S., Hodgson, V., & McConnell, D. (2004). Research on networked learning: An overview Advances in research on networked learning (pp. 1-9): Springer.

Henderson, R., Noble, K., & Cross, K. (2013). Additional professional induction strategy (APIS): Education Commons, a strategy to support transition to the world of work.

Herrington, A., Herrington, J., Kervin, L., & Ferry, B. (2006). The design of an online community of practice for beginning teachers. Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 6(1), 120-132.

Ingersoll, R. M., & Strong, M. (2011). The Impact of Induction and Mentoring Programs for Beginning Teachers A Critical Review of the Research. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 201-233.

Ito, M., Gutierrez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes, J., Salen, K., . . . Watkins, S. C. (2013). Connected learning: An agenda for research and design: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Kelly, N. (2013). An opportunity to support beginning teachers in the transition from higher education into practice. Paper presented at the ASCILITE 2013, Macquarie University, Australia.

Kelly, N., Reushle, S., Chakrabarty, S., & Kinnane, A. (2014). Beginning Teacher Support in Australia: Towards an Online Community to Augment Current Support. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4), 4.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation: Cambridge university press.

Lee, K., & Brett, C. (2013). What are student inservice teachers talking about in their online Communities of Practice? Investigating student inservice teachers’ experiences in a double-layered CoP. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 21(1), 89-118.

Lin, F.-r., Lin, S.-c., & Huang, T.-p. (2008). Knowledge sharing and creation in a teachers’ professional virtual community. Computers & Education, 50(3), 742-756. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2006.07.009

Maher, D., Sanber, S., Cameron, L., Keys, P., & Vallance, R. (2013). An online professional network to support teachers’ information and communication technology development. Paper presented at the ASCILITE 2013, Macquarie University.

Mamykina, L., Manoim, B., Mittal, M., Hripcsak, G., & Hartmann, B. (2011). Design lessons from the fastest q&a site in the west. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems.

Shirky, C. (2010). Cognitive surplus: Creativity and generosity in a connected age: ePenguin.

Veenman, S. (1984). Perceived problems of beginning teachers. Review of Educational Research, 54(2), 143-178.

Wenger, E. (2011). Communities of practice: A brief introduction.

Wenger, E., White, N., & Smith, J. D. (2009). Digital habitats: Stewarding technology for communities: CPsquare.

[1] For details of the ongoing project see http://www.stepup.edu.au