I recently published a paper, along with co-authors Marcela Cespedes, Marc Clarà and Patrick Danaher, that does some important research to help address this overarching question of why Australian early career teachers leave the profession. It focuses on the complex relationships among preservice education, early career support, and job satisfaction, and how these impact upon intention to leave the profession. You can cheat and jump to the whole paper here [open access] which should be relevant for anyone interested in early career teacher attrition and retention.

The paper is asking four key questions:

- How (if at all) does the kind of preservice education a teacher receives relate to early career teachers’ intentions to leave the profession?

- How (if at all) does the early career support received relate to early career teachers’ intentions to leave the profession?

- How (if at all) does job satisfaction relate to early career teachers’ intention to leave the profession?

- The sub-questions of: are any kinds of preservice education or early career support associated with increased job satisfaction for early career teachers?

The abstract of the paper sums it up, and then I’ll unpack some of the key findings from the paper:

This paper investigates the complex factors that lead to early career teachers (ECTs) deciding to leave the profession. It extends prior studies to show the associations that different elements of preservice education (PSE), early career support, and on-the-job satisfaction have with the intention to leave the profession. The study uses data from 2,144 Australian ECTs to explore these relationships. Results highlight the importance of teachers’ collegial relationships with their peers, and replicate prior findings showing the significance of mentoring and induction programs. Results show that elements of job satisfaction are strongly associated with intention to leave the profession, leading to a number of implications for achieving the twin goals of higher teacher retention and job satisfaction.

Key definitions and notes on data sources and analysis

I should add that we define early career teachers as those in their first five years. The data come from the Staff in Australia’s Schools Dataset and I am grateful for the Australian Data Archive for making this dataset available to me (see the paper for the exact data item).

In all that follows note that we had an excellent sample size thanks to the SiAS (2,144 early career teachers), but note also that our data come from 2010. All of the findings below follow use of regression to account for the possible influence of demographics, such as rural/provincial/metro, primary/secondary divide, and catholic/independent/state school systems.

What we found

There were a real mix of findings in response to these questions. I’ll just highlight the key ones here:

- How (if at all) does the kind of preservice education a teacher receives relate to early career teachers’ intentions to leave the profession?

We found that there were two factors in preservice education that were significant in that they were associated with teachers who did not want to leave the profession: feeling prepared for working with other teachers, and feeling prepared for teaching diverse learners.

It follow that perhaps (although I note that the research is only preliminary evidence to support this idea) one way to improve teacher retention is to focus on these two areas in teacher education: working well with other teachers, and teaching diverse learners. It is interesting on this note that Diane Mayer and her team in the Studying Effective Teaching project found that collaboration and collegiality were not well taught in teacher education programs.

- How (if at all) does the early career support received relate to early career teachers’ intentions to leave the profession?

In keeping with the literature we found that having a helpful mentor (not just any old mentor!) and enabling structured discussions significantly predicted ECTs’ retention. We were also able to look at the statistical relationship between having these kinds of support and the likelihood that a teacher intended to leave the profession. As it says in the paper:

…for those with helpful (rather than unhelpful) designated mentors, the odds of staying in the profession were between 35% and 122% higher. There was a smaller effect, of between 11% to 96% increase in the odds of ECT responding “no” to intention to leave, when designated mentors were helpful when compared with not received mentoring

Once again, this suggests that schools and school systems should focus upon providing these areas of support. This is not a new findings, but it provides strong empirical evidence to support something that was already demonstrated by people like DeAngelis and Ingersoll, and shows that it holds true in the Australian context.

- How (if at all) does job satisfaction relate to early career teachers’ intention to leave the profession?

It is fairly a obvious proposition that teachers who are satisfied with their jobs are less likely to want to leave the profession, and that’s exactly what we found. What makes this interesting is that we looked at which areas of job satisfaction mattered the most, as well as looking at how they impacted the odds that a teacher wanted to leave the profession.

Firstly, we found that those who were overall satisfied with their job were between 4 and 9 times as likely to not be intending to leave the profession (i.e., we infer that they were more likely to stay).

Secondly, we found that the areas of job satisfaction that mattered most (see the paper for the full list of areas of job satisfaction considered) were:

- the amount of teaching required

- the amount of clerical/administrative work required

- what teachers were accomplishing with students

- the value that society places on teachers’ work

- the relationships with parents/guardians

This is interesting, because it supports existing research into which areas of the job matter most for retention, and contributes to the solid empirical foundation. It supports the idea that trying to improve teacher retention cannot be achieved by extrinsic rewards like salary alone.

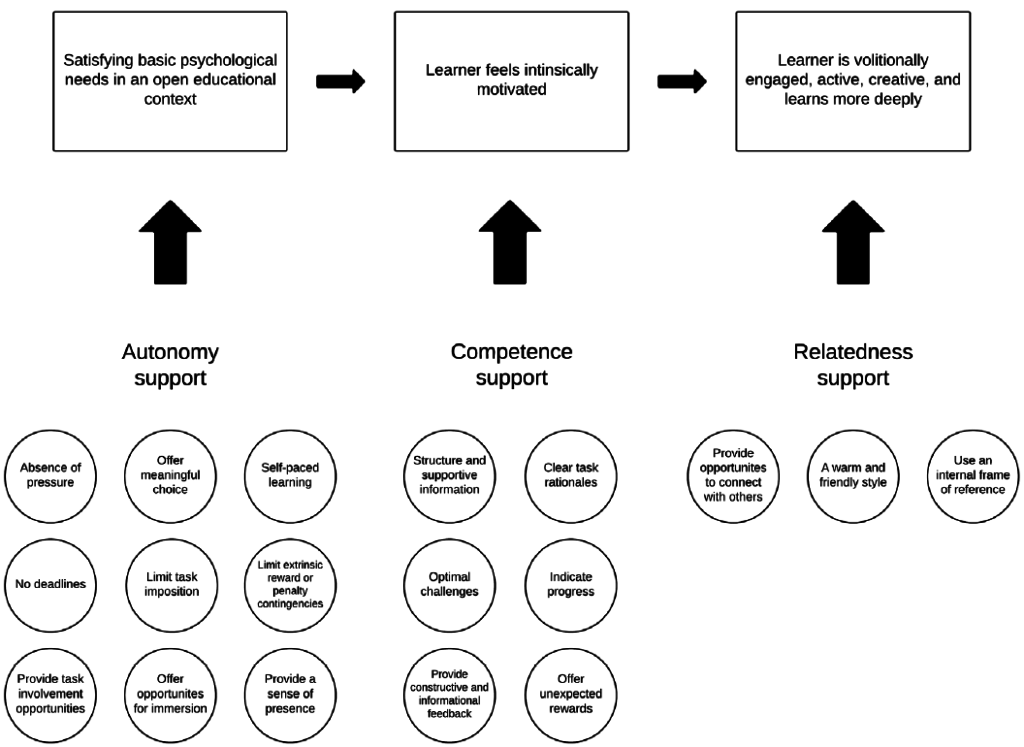

Rather, it speaks to the notion that teachers need support for intrinsic motivation. I hope in future work to analyse these findings through the lens of Self-Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci, 2000) as I believe that this finding is all about teachers needing to have their basic psychological needs supported, namely:

- Support for teacher competence (having enough time and training to achieve everything that needs to be done)

- Support for teacher relationality (structures that support relationships between teachers and with parents as a key part of the job)

- Support for autonomy (having enough time and freedom to do the job in a way that is true to teachers’ beliefs)

References

DeAngelis, K. J., Wall, A. F., & Che, J. (2013). The impact of preservice preparation and early career support on novice teachers’ career intentions and decisions. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(4), 338-355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487113488945

Ingersoll, R. M., & Strong, M. (2011). The impact of induction and mentoring programs for

beginning teachers: A critical review of the research. Review of Educational

Research, 81(2), 201-233. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311403323

Kelly, N., Cespedes, M., Clarà, M., & Danaher, P. A. (2019). Early career teachers’ intentions to leave the profession: The complex relationships among preservice education, early career support, and job satisfaction. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(3).

http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v44n3.6

Kelly, N., Sim, C., & Ireland, M. (2018). Slipping through the cracks: teachers who miss out

on early career support. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 1-25.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2018.1441366

Mayer, D., Dixon, M., Kline, J., Kostogriz, A., Moss, J., Rowan, L., . . . White, S. (2017).

Studying the effectiveness of teacher education. In D. Mayer, M. Dixon, J. Kline, A.

Kostogriz, J. Moss, L. Rowan, B. Walker-Gibbs, & S. White (Eds.), Studying the

effectiveness of teacher education: Early career teachers in diverse settings (pp. 13-

26). Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-3929-4