I had the great pleasure of working with Neil Martin over a number of years, during his project investigating the way that the principles of Self-Determination Theory (SDT) can be applied for designing engaging online courses.

I’m forever grateful to Neil for getting me to read deeply about positive psychology–the branch of psychology trying to understand the conditions under which humans flourish.

In particular, I find the work of Richard Ryan and Edward Deci to be extremely elegant, putting this research into human flourishing (or, as it’s referred to, eudaimonia) on solid scientific ground. I thoroughly recommend this paper for anyone wanting a scholarly introduction to the idea of why not all kinds of motivation are equal, regardless of behavioural outcomes.

This post aims to give a brief overview of a paper that Neil led–and very kindly invited me to be a part of–describing the work from his PhD thesis in developing a MOOC in which every part of the design was informed by thinking about intrinsic motivation from the perspective of SDT.

I feel like the resulting paper (Martin, Kelly, & Terry, 2018) really has a lot in it, and may well be of help to anyone who is doing work designing an online course and wants students to be more engaged.

(It is also worth mentioning that I quite enjoyed the fact that all three authors have last names that are also first names. It makes me feel like I have at least one thing in common with Elton John, George Michael and Buddy Holly)

Principles for designing engaging online courses

Some principles for designing engaging online courses can be distilled.

The essential principle of self-determination theory, when applied to motivating people to doing a task, is that human intrinsic motivation has three elements:

- Competence. People tend to feel intrinsically motivated for a task if they feel like they have the ability needed to successfully complete the task. In other words, people like the feeling of being good at something.

- Relatedness. People tend to feel more intrinsically motivated for a task if they feel that completing the task will, in some way (either direct or indirect), help to connect them with other human beings. In short, people like feeling as though they are developing a relationship with other people.

- Autonomy. Autonomy is about giving people the freedom to complete a task in a way that is in harmony with their beliefs about the world, to do things in a way that makes sense to them and fits in with their life.

This is, of course, a gross oversimplification of what is a deep theory with decades of research behind it (see http://selfdeterminationtheory.org/ for a nicely curated website about SDT).

Neil’s work (his PhD is available here and well worth a read for anyone wanting to go much deeper) demonstrated that these principles–of achieving intrinsic motivation of students through support for relatedness, autonomy, and competence–can be applied directly to learning design for online courses.

He found fairly convincing evidence in his work that the students were more engaged with the course, and more likely to complete the course, once it had been redesigned based upon these principles–and as anyone who has tried to make a MOOC knows, getting students to begin the course is one thing, but getting them to complete it is much more challenging!

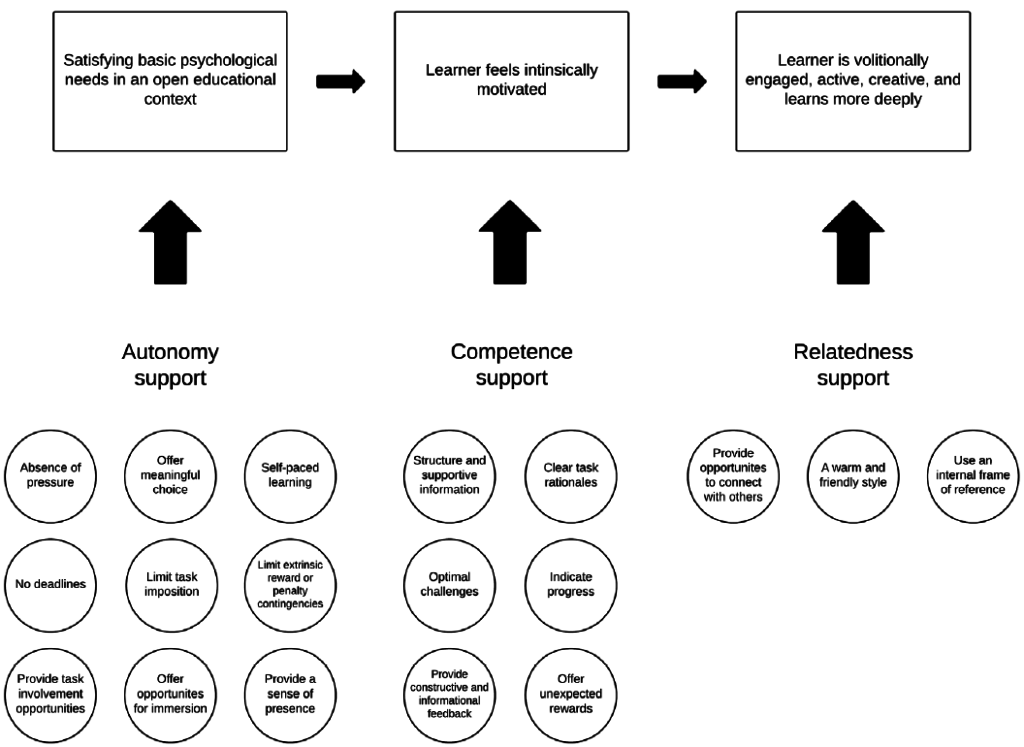

The figure below is from Martin et al. (2018) and is a summary of what I would call a model for designing engaging online courses. The premise is that if students have their basic psychological needs met, then they will be more engaged with the learning.

The paper (freely available thanks to the excellent online journal AJET) goes into detail about what all of these things mean and describes this model in detail. It makes a bridge between these three basic psychological needs and what this means in practice when designing for online learning. Some examples:

Autonomy

- Not having deadlines and reducing pressure

- Letting participants set their own pace

- Giving participants meaningful choices wherever possible

Competence

- Making sure that challenges are optimal (i.e., are within the zone of proximal development)

- Giving clear rationale for any task

- Providing constructive feedback on tasks

Relatedness

- Making sure that the text and interface design of the online course is warm and friendly

- Making sure that participants have an opportunity to connect with each other

- This can be done by learning designers by making use of personas (refer to Martin 2017 for more details on this)

I’m writing this post now because I’m finding this to be a big help in some course redesign work that I am doing with La Trobe university, in their MTEACH course.

Hopefully the result will be lots of engaged students!

References